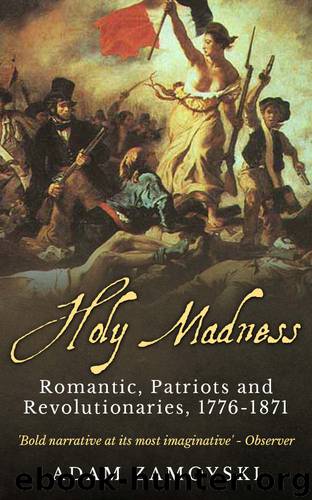

Holy Madness: Romantics, Patriots and Revolutionaries, 1776-1871 by Adam Zamoyski

Author:Adam Zamoyski [Zamoyski, Adam]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Endeavour Press

Published: 2014-10-20T22:00:00+00:00

Chapter Fourteen – Glory Days

‘People and poets are marching together,’ wrote the French critic Charles Augustín Sainte-Beuve in 1830. ‘Art is henceforth on a popular footing, in the arena with the masses.’[352] There was something in this. Never before or since had poetry been so widely and so urgently read, so taken to heart and so closely studied for hidden meaning. And it was not only in search of aesthetic or emotional uplift that people did so, for the poet had assumed a new role over the past two decades. Art was no longer an amenity but a great truth that had to be revealed to mankind, and the artist was one who had been called to interpret this truth, a kind of seer. In Russia, Pushkin solemnly declared the poet’s status as prophet uttering the burning words of truth. The American Ralph Waldo Emerson saw poets as ‘liberating gods’ because they had achieved freedom themselves, and could therefore free others.[353] The pianist and composer Franz Liszt wanted to recapture the ‘political, philosophical and religious power’ that he believed music had in ancient times.[354] William Blake claimed that Jesus and his disciples were all artists, and that he himself was following Jesus through his art.[355] ‘God was, perhaps, only the first poet of the universe,’ Théophile Gauthier reflected.[356] By the 1820s artists regularly referred to their craft as a religion, and Victor Hugo represented himself alternately as Zoroaster, Moses and Christ, somewhere between prophet and God.

Social man’s natural reaction to repression and censorship is to transfer his thoughts to a medium other than words or one in which words can have a double meaning. Parallel modes of expression, visual and aural, spring up to serve the need for communication, comprehensible to all yet difficult for the censor to nail down and condemn. The debate that should be conducted in the open with plain words is simply transferred to another forum, one far more dangerous for the authorities, as it denies them the possibility of any response but that of outright prohibition. Thus the arts followed the secret societies in becoming a political means of communication and the expression of a political faith. Heinrich Heine once declared that he did not mind whether he was remembered as a poet. ‘But a sword should be laid on my bier, for I have been a steadfast soldier in the war of liberation of humanity,’ he insisted.[357]

In the repressive climate of post-1815 Europe, poetry and music served this purpose best, particularly in forms where they came together. The chansonnier poets were powerful manipulators of public opinion in Restoration France, and the increasingly popular form of opera was to take this role further still. It became the platform not for disseminating information or views, but for generating mood and feeling, and a marshalling ground for their active expression. There was much that was ironic in this, since opera as an art form grew out of court masques and entertainments aimed at the glorification of the monarch.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

Cat's cradle by Kurt Vonnegut(15362)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(14517)

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(12398)

Underground: A Human History of the Worlds Beneath Our Feet by Will Hunt(12100)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(12033)

Wiseguy by Nicholas Pileggi(5791)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(5452)

Perfect Rhythm by Jae(5409)

American History Stories, Volume III (Yesterday's Classics) by Pratt Mara L(5310)

Paper Towns by Green John(5194)

Pale Blue Dot by Carl Sagan(5012)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4965)

The Mayflower and the Pilgrims' New World by Nathaniel Philbrick(4506)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(4492)

Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI by David Grann(4449)

The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen(4396)

Too Much and Not the Mood by Durga Chew-Bose(4349)

The Borden Murders by Sarah Miller(4329)

Sticky Fingers by Joe Hagan(4204)